Totally bounded space

In topology and related branches of mathematics, a totally bounded space is a space that can be covered by finitely many subsets of any fixed "size" (where the meaning of "size" depends on the given context). The smaller the size fixed, the more subsets may be needed, but any specific size should require only finitely many subsets. A related notion is a totally bounded set, in which only a subset of the space needs to be covered. Every subset of a totally bounded space is a totally bounded set; but even if a space is not totally bounded, some of its subsets still will be.

The term precompact (or pre-compact) is sometimes used with the same meaning, but `pre-compact' is also used to mean relatively compact. In a complete metric space these meanings coincide but in general they do not. See also use of the axiom of choice below.

Contents |

Definition for a metric space

A metric space  is totally bounded if and only if for every real number

is totally bounded if and only if for every real number  , there exists a finite collection of open balls in

, there exists a finite collection of open balls in  of radius

of radius  whose union contains

whose union contains  . Equivalently, the metric space

. Equivalently, the metric space  is totally bounded if and only if for every

is totally bounded if and only if for every  , there exists a finite cover such that the radius of each element of the cover is at most

, there exists a finite cover such that the radius of each element of the cover is at most  . This is equivalent to the existence of a finite ε-net.

. This is equivalent to the existence of a finite ε-net.

Each totally bounded space is bounded (as the union of finitely many bounded sets is bounded), but the converse is not true in general. For example, an infinite set equipped with a discrete metric is bounded but not totally bounded.

If M is Euclidean space and d is the Euclidean distance, then a subset (with the subspace topology) is totally bounded if and only if it is bounded.

Definitions in other contexts

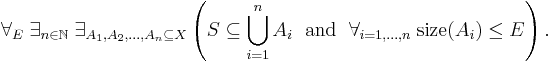

The general logical form of the definition is: A subset S of a space X is a totally bounded set if and only if, given any size E, there exist a natural number n and a family A1, A2, ..., An of subsets of X, such that S is contained in the union of the family (in other words, the family is a finite cover of S), and such that each set Ai in the family is of size E (or less). In mathematical symbols:

The space X is a totally bounded space if and only if it is a totally bounded set when considered as a subset of itself. (One can also define totally bounded spaces directly, and then define a set to be totally bounded if and only if it is totally bounded when considered as a subspace.)

The terms "space" and "size" here are vague, and they may be made precise in various ways:

A subset S of a metric space X is totally bounded if and only if, given any positive real number E, there exists a finite cover of S by subsets of X whose diameters are all less than E. (In other words, a "size" here is a positive real number, and a subset is of size E if its diameter is less than E.) Equivalently, S is totally bounded if and only if, given any E as before, there exist elements a1, a2, ..., an of X such that S is contained in the union of the n open balls of radius E around the points ai.

A subset S of a topological vector space, or more generally topological abelian group, X is totally bounded if and only if, given any neighbourhood E of the identity (zero) element of X, there exists a finite cover of S by subsets of X each of which is a translate of a subset of E. (In other words, a "size" here is a neighbourhood of the identity element, and a subset is of size E if it is translate of a subset of E.) Equivalently, S is totally bounded if and only if, given any E as before, there exist elements a1, a2, ..., an of X such that S is contained in the union of the n translates of E by the points ai.

A topological group X is left-totally bounded if and only if it satisfies the definition for topological abelian groups above, using left translates. That is, use aiE in place of E + ai. Alternatively, X is right-totally bounded if and only if it satisfies the definition for topological abelian groups above, using right translates. That is, use Eai in place of E + ai. (In other words, a "size" here is unambiguously a neighbourhood of the identity element, but there are two notions of whether a set is of a given size: a left notion based on left translation and a right notion based on right translation.)

Generalising the above definitions, a subset S of a uniform space X is totally bounded if and only if, given any entourage E in X, there exists a finite cover of S by subsets of X each of whose Cartesian squares is a subset of E. (In other words, a "size" here is an entourage, and a subset is of size E if its Cartesian square is a subset of E.) Equivalently, S is totally bounded if and only if, given any E as before, there exist subsets A1, A2, ..., An of X such that S is contained in the union of the Ai and, whenever the elements x and y of X both belong to the same set Ai, then (x,y) belongs to E (so that x and y are close as measured by E).

The definition can be extended still further, to any category of spaces with a notion of compactness and Cauchy completion: a space is totally bounded if and only if its completion is compact.

Examples and nonexamples

- A subset of the real line, or more generally of (finite-dimensional) Euclidean space, is totally bounded if and only if it is bounded. Archimedean property is used.

- The unit ball in a Hilbert space, or more generally in a Banach space, is totally bounded if and only if the space has finite dimension.

- Every compact set is totally bounded, whenever the concept is defined.

- Every totally bounded metric space is bounded. However not every bounded metric space is totally bounded.[1]

- A subset of a complete metric space is totally bounded if and only if it is relatively compact (meaning that its closure is compact).

- In a locally convex space endowed with the weak topology the precompact sets are exactly the bounded sets.

- A metric space is separable if and only if it is homeomorphic to a totally bounded metric space.[1]

- An infinite metric space with the discrete metric (the distance between any two distinct points is 1) is not totally bounded, even though it is bounded.

Relationships with compactness and completeness

There is a nice relationship between total boundedness and compactness:

Every compact metric space is totally bounded.

A uniform space is compact if and only if it is both totally bounded and Cauchy complete. This can be seen as a generalisation of the Heine-Borel theorem from Euclidean spaces to arbitrary spaces: we must replace boundedness with total boundedness (and also replace closedness with completeness).

There is a complementary relationship between total boundedness and the process of Cauchy completion: A uniform space is totally bounded if and only if its Cauchy completion is totally bounded. (This corresponds to the fact that, in Euclidean spaces, a set is bounded if and only if its closure is bounded.)

Combining these theorems, a uniform space is totally bounded if and only if its completion is compact. This may be taken as an alternative definition of total boundedness. Alternatively, this may be taken as a definition of precompactness, while still using a separate definition of total boundedness. Then it becomes a theorem that a space is totally bounded if and only if it is precompact. (Separating the definitions in this way is useful in the absence of the axiom of choice; see the next section.)

Use of the axiom of choice

The properties of total boundedness mentioned above rely in part on the axiom of choice. In the absence of the axiom of choice, total boundedness and precompactness must be distinguished. That is, we define total boundedness in elementary terms but define precompactness in terms of compactness and Cauchy completion. It remains true (that is, the proof does not require choice) that every precompact space is totally bounded; in other words, if the completion of a space is compact, then that space is totally bounded. But it is no longer true (that is, the proof requires choice) that every totally bounded space is precompact; in other words, the completion of a totally bounded space might not be compact in the absence of choice.

Notes

References

- Willard, Stephen (2004). General Topology. Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-43479-6.